Recently, dedicated radio listeners were surprised by the announcement that radio stations in Europe and the United States intend to drag out turntables to play vinyl LPs, invoking the supposed “warmth” some self-described audiophiles associate with an LP’s sound.

For those of us with a long memory, the news came as a reminder of how before the digitization of audio 40 years ago, recording engineers and DJs in a radio station control room would use at least two turntables and two or three tape recorders in their everyday routine. Philips and Sony then gave us the Compact Disc — a new type of digital “gramophone record,” heralding a new era of mass communication and consumerism. It was the biggest breakthrough in sound reproduction since Thomas Edison invented the phonograph in 1877.

Consequently, radio stations gradually phased out vinyl single and LP records in the mid-1980s and went to CDs. Huge turntables and tape recorders the size of electric cookers disappeared, replaced by small CD players. As far as the sound quality was concerned, CDs eliminated a number of problems such as clicks and pops and occasionally the embarrassment of a stuck needle — and listeners could hear the benefits over the radio.

Those pops and clicks

On a well-maintained record, pops and clicks are often not audible and should therefore not distract from the listening experience. However, no evidence exists of a record with absolutely no pops or clicks. They are introduced at virtually every stage of vinyl production, from cutting the lacquer to the pressing and playback — more often, the result of static discharges. Although topical treatments on the record may mitigate this effect, they cannot eliminate it. With use, and over time, groove wear is inevitable. The pops and clicks that result are noticeable at higher frequencies, and even using an expensive, modern pick-up and stylus cannot solve the problem.

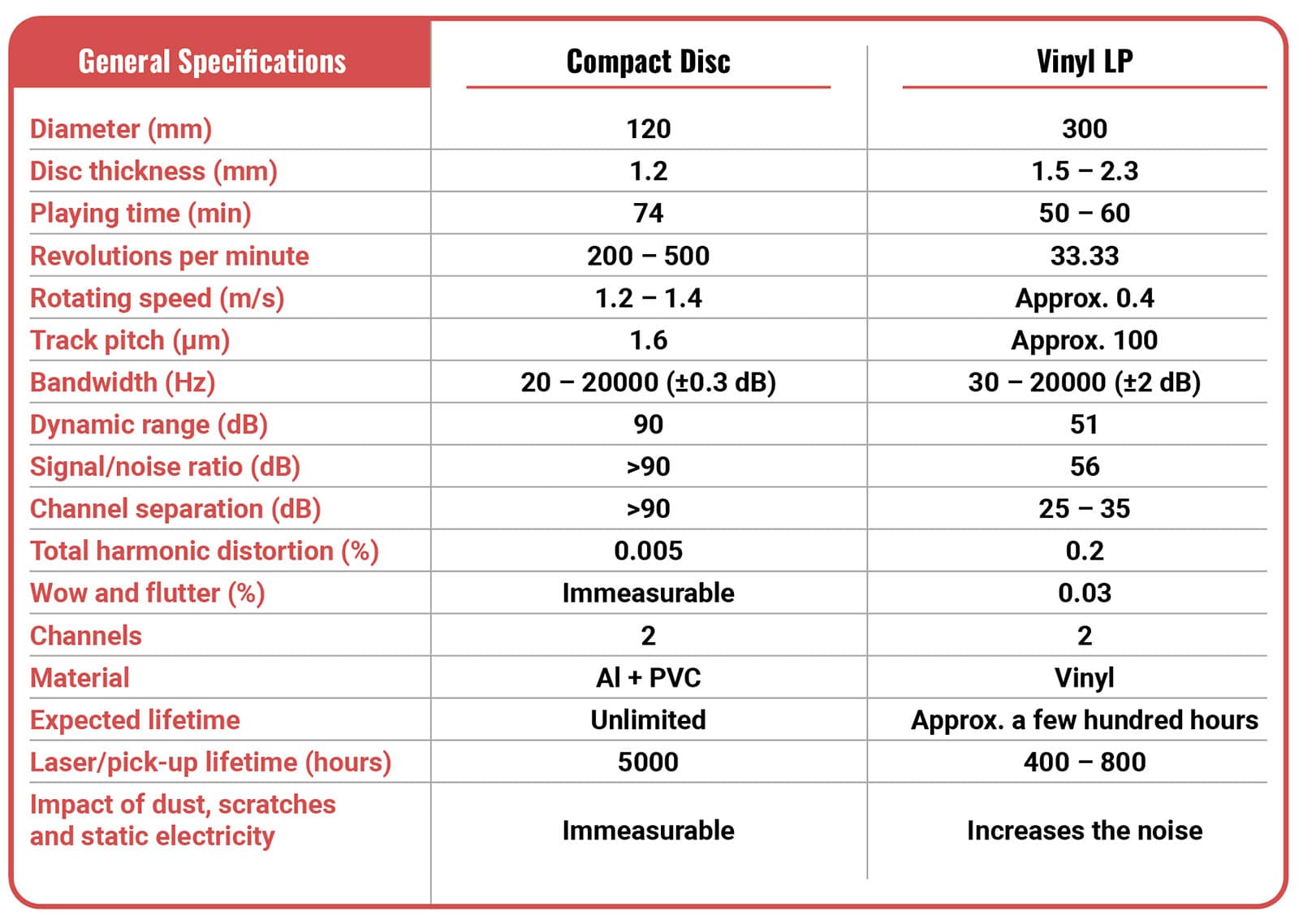

A compact disc digital audio system, on the other hand, utilizes a laser optical pick-up with a unique high-density recorded disc. As shown in Table 1, the main advantages of a CD compared to a vinyl LP are a broad bandwidth allowing a frequency response characteristic of 20,000 Hz, impressive signal-to-noise ratio, excessive dynamics ratio and immeasurable wow and flutter, with an extremely low percentage of harmonic distortion.

No evidence exists of a record with absolutely no pops or clicks.

The overall result is a quality of digitally recorded and reproduced sound that is a step closer to achieving the faithful representation of the sound at the scene of recording, be it a concert hall or studio.

Music lovers, musicians and radio and television professionals greeted the CD format with open arms, happy to finally enjoy quality in a source of recorded sound that would not deteriorate through years of everyday use.

On a theoretical level, there’s, therefore, no reason to consider the case that vinyl sounds better. There are built-in problems with using vinyl as a data encoding mechanism with no CD equivalent. Vinyl is physically limited by the fact that records have to be capable of being played without skipping or causing distortion. This both limits the dynamic range — the difference between the loudest and softest note — and the range of pitches of the frequencies of sound one can hear. If the sound gets too low in pitch, less audio can fit in a given amount of vinyl. If the sound is too high, the stylus has difficulty tracking it, causing distortion. So, engineers mastering for vinyl often cut back on extreme high or low ends, using a variety of methods, all of which alter the music.

The final verdict

Nevertheless, today, some people prefer listening to music on vinyl rather than on CD or other digital formats. Their reasons should have nothing to do with actual sound quality but more with the tactile characteristics of vinyl, visual aspects such as larger album artwork and the playback ritual. Others prefer listening to CDs for a different set of reasons. There is nothing wrong with preferring vinyl to CDs, MP3 and digital audio in general, as long as the preference is honestly stated on emotional terms, or is precisely quantified and tied to subjective experience, and not obscured with erroneous and sometimes pejorative technical appeals.

Their reasons should have nothing to do with actual sound quality but more with the tactile characteristics of vinyl, visual aspects such as larger album artwork and the playback ritual.

As for the “warmth” of vinyl, that can generally be ascribed to a less accurate bass sound. The difficulty of accurately translating bass lines to vinyl without making grooves too big means that engineers have to do a lot of processing to get it to work, which changes the tone of the bass in a way that, apparently, many people find aesthetically pleasing.

For audio professionals, however, the arbitrary claims that the sound impression of LPs compared to CDs is allegedly superior is as acceptable as a claim that traveling from Paris to Brussels is more comfortable in a four-horse chariot than in the latest model Tesla.

The author is a retired acoustics engineer with 47 years of experience. His newest book “Acoustical Design of Broadcasting and Recording Studios” is published and available on Amazon.