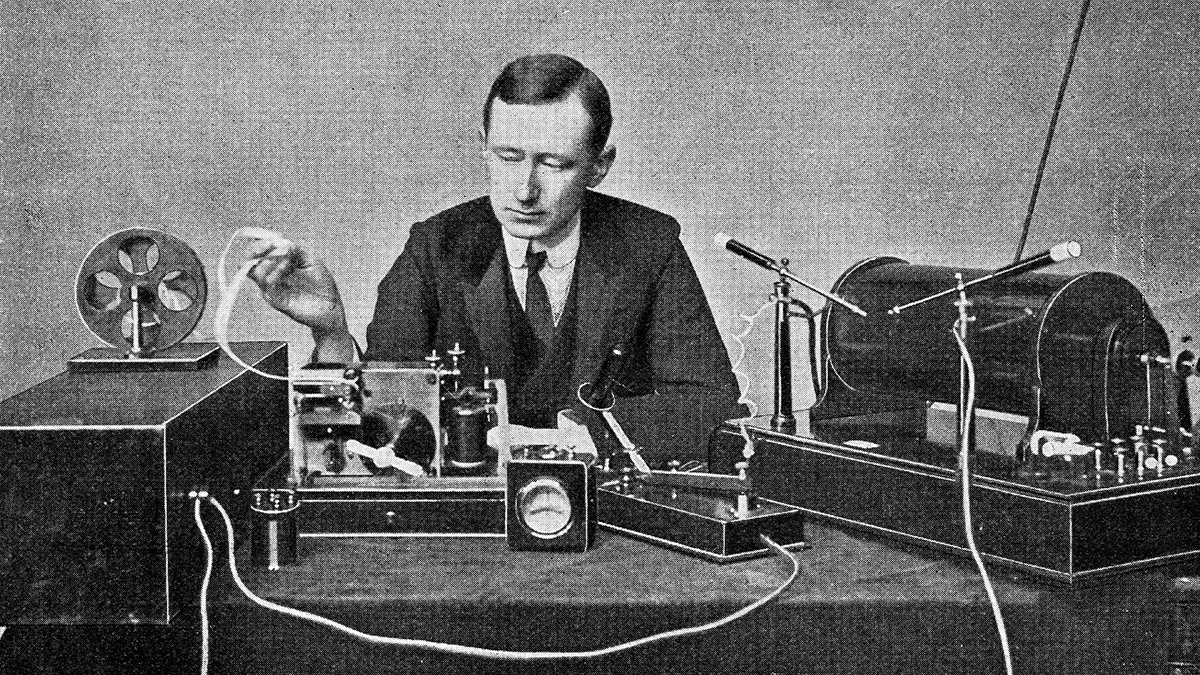

Radio as a medium took an important scientific discovery and revolutionized how people communicated and entertained. It built on the work of German physicist Heinrich Hertz in proving radio waves existed that enabled Guglielmo Marconi to create a communications system used around the world.

This process began when Marconi took out the first patent for wireless telegraphy in June 1896. The following year, he founded the Wireless Telegraph and Signal Company, Limited, in London, changing the name in 1900 to Marconi’s Wireless Telegraph Company, and building a six-kilowatt longwave transmitter in Chelmsford, England. From there, he broadcast half-hour programs of news, music and gramophone recordings every day starting on February 23, 1920.

In May of that same year, the first London radio station, 2LO, run by Marconi’s company, went on air from a studio on the Strand. The newly formed British Broadcasting Company, Limited, later took over the station’s running operations in November 1922. The chief engineer was PP (Peter Pendleton) Eckersley, who had earlier worked for Marconi as both a broadcaster and head of his experimental section.

Despite helping establish the BBC’s radio network, Eckersley was pushed into resigning in 1929, due to a divorce scandal, by John Reith, the principled director-general of what, two years earlier, had become the British Broadcasting Corporation. Eckersley later designed a broadcast station for the International Broadcasting Company (IBC), set up by Captain Leonard Plugge in 1930 to broadcast sponsored programming from the European continent to Britain.

The iconic “mic”

While the transmitter may symbolize early radio, the modern image is that of a presenter at the microphone. The first device with proper voice reproduction was the carbon “mic,” independently and separately developed by Thomas Edison, David Edward Hughes and Emile Berliner. Edison patented the design in 1877, after a legal tussle.

Further developments came during the early 20th century, with the first condenser mic, designed by E.C. Wente in 1916. The next breakthrough was in 1923, with the appearance of the Marconi-Sykes magnetophone, designed by Captain Henry Joseph Round, the first chief engineer of the Marconi’s Wireless Telegraph Company. Known as the “meat safe” due to the wooden frame and mesh covering needed to suspend its highly sensitive moving coil, it became the standard mic at the BBC’s London studios. It was also used for the first-ever radio outside broadcast at 10:30 pm on May 19, 1924 in the Surrey village of Oxted, when Miss Beatrice Harrison played her cello to encourage a nightingale into song. The BBC recently revealed that the first broadcast had to be faked using a bird impersonator because any nightingales around had been scared off by the OB crew.

While development continued on moving coil mics, a new technology came in the form of the ribbon mic. This was introduced in 1923 and is usually attributed to RCA Victor engineer Harry F. Olson. The BBC showed interest in this technology, but felt the RCA model 44 was too expensive. Instead, it worked with Marconi to produce the Type-A in 1934. The mic’s distinctive lozenge shape was strongly associated with BBC radio, featuring in many publicity pictures. The BBC used the mic up to the late 1950s. In the United States, it was the Shure Unidyne model 55, designed in 1937 by engineer Benjamin Bauer, that became equally iconic. It is probably best known today for being used by Robin Williams as DJ Adrian Cronauer in “Good Morning, Vietnam.”

Recording the magic

In those early days, radio was considered an ephemeral medium, even though the technology for recording programs was available from 1928. Productions were cut onto 78 rpm discs for both syndication and archiving, but the quality was variable. Several discs were needed for one show until Alan Blumlein, an EMI engineer, made considerable improvements to disc cutters. Blumlein was an audio pioneer, and is generally credited as the inventor of stereo, and contributed to the development of microphones.

The real breakthrough in recording technology came with the wide-scale availability of magnetic tape-based recorders. Fritz Pfleumer’s 1928 development of oxide powder on paper tape led to the first practical tape recording machine: The Magnetophon K1. It appeared in 1935, developed by AEG and BASF. Parallel work went on in the U.S., but a key moment was when American engineer John T. Mullin brought two Magnetophons and 50 reels of tape back from Germany toward the end of World War II. Mullin refined the machines and demonstrated taped performances that people, apparently, believed sounded live.

The real breakthrough in recording technology came with the wide-scale availability of magnetic tape-based recorders.

Bing Crosby, one of the most prominent singing and film stars of the time, heard about this and arranged a private demo. Crosby had been looking for a way to record his radio shows for NBC, and found disc transcription unsatisfactory. Using Mullin’s improved techniques, Crosby’s 1947 radio series became the first taped broadcasts in the U.S. The star later invested in the electronics firm Ampex, which produced the game-changing Model 200 tape machine.

Tape enabled efficient recording and distribution of programs, and allowed radio journalists to interview people on location, using portable machines such as the Uher, and then edit the material into concise reports. In a sideways development, tape helped create one of the iconic pieces of radio equipment — the jingle/ad cartridge. Officially called the Fidelipac, it is better known as the NAB “cart” and was patented in 1954 by George Eash, building on the earlier invention of the endless tape loop by Bernard Cousino (although the Automatic Tape Company also claims credit for the Fidelipac).

The cart machine became ubiquitous in radio. It was a mainstay of commercial AM stations in the U.S. during the 1940s and 50s, and, together with the microphone, formed the backbone of radio during its Golden Age.

Part two of this look at radio innovations will pick up with FM broadcasting and look at the coming of the digital and computer age.